Related

Quick Links

Don’t trust everything you see on LinkedIn.

We created a fake LinkedIn profile with a fake job at a real company.

Our fake profile garnered the attention of a Google recruiter and gained over 170 connections and 100 skill endorsements.

Everyone is talking about fake accounts on Facebook and fake followers on Twitter.

LinkedIn Doesn’t Verify Anything

We created a fake profile and connected it to a real company.

Sadly, it isn’t hard.

LinkedIn doesn’t ask for any proof or confirmation of anything.

Instead, LinkedIn runs on a sort of honor system.

you might say you work for a large company and give yourself an impressive job title.

It worked for us.

Our fake profile (John) “works for HP” as an Innovation Technologist.

We also gave John previous jobs at Exabeam and Salesforce to round out his resume.

You might imagine that HP or someone else would notice and stop us.

But that’s not how it works.

LinkedIn doesn’t notify companies about new employee profiles.

We didn’t steal anyone’s identity or even use a real photo for our fake profile.

See that photo of John?

That’s not a stock photo of a real person.

Instead, the image came fromthispersondoesnotexist.com.

Simply put, it’s a fake photo of a non-existent person generated by a computer algorithm.

Here’s ascreenshotof the fake profile for posterity.

That makes the odds of getting caught AND getting removed incredibly low.

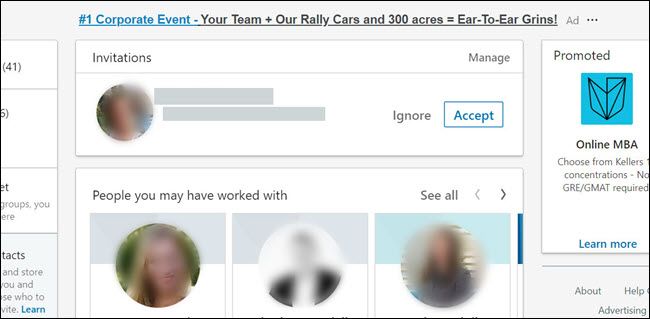

To solve it, we started randomly trying to connect to any HP employee we could find.

We didn’t have a single legitimate connection to invite, which was a problem.

But all we needed was one person to say yes.

After the first person connected, the process took off.

Before we knew it, with just an hour or two of work, John had nearly 50 connections.

But no one noticed John wasn’t real.

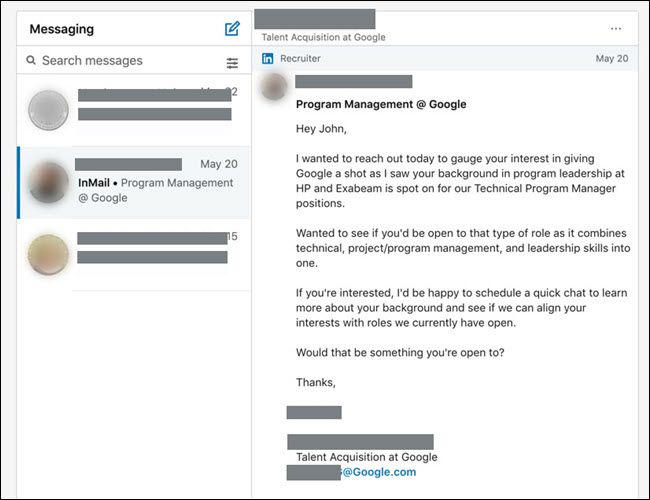

Instead, Google thought he might be a good fit for a job.

And so a Google recruiter reached out.

As far as the Google employee was concerned, there were no red flags with John.

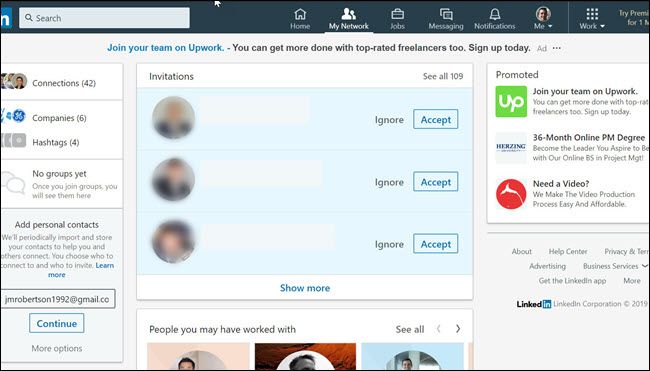

But that’s too much work.

We wanted a lot of connections fast.

So we used a shortcut.

We paid for a service that gave John 100 connections.

Those connections then endorsed our ten top skills, giving us a total of 100 endorsements.

Not surprisingly, we found our invitation requests answered more quickly once the connection numbers grew so large.

Now John’s profile looks impressive!

You may wonder whether LinkedIn will notice we paid for connections.

As far as we can tell, they’re “valid.”

That’s what the service promised, too.

They have work experience and educational background.

From what we can see, this is an automated process.

The 100 connection invites came in almost simultaneously.

The endorsement process used the existing connections we paid for.

The connection-buying service maintains ongoing access to all these profiles.

If you’re connected directly to someone, that’s afirst-degree connection.

Your connections' connections that you don’t share are second-degree connections.

And any connections they have are third-degree connections.

As you build up personal connections, your extended web link proliferates.

It’s a small world, after all.

“This person knows a friend of a friend” is supposed to be reassuring.

But you could’t count on that.

There’s no way to trace your connections to that person, either.

LinkedIn Provides an Illusion of Trustworthiness

LinkedIn’s problems are numerous.

But most of those issues are small and forgivable on their own.

Anyone can create a profile with any name.

Anyone can list themselves as an employee of any company.

LinkedIn doesn’t provide companies an easy way to moderate and enforce its employee roster.

Anyone can buy connections and endorsements.

On their own, any one of those statements isn’t a significant problem.

But, added together, the problem is much bigger than the total of the parts.

No one is verifying accuracy; it all relies on an honor system.

When you receive a connection request, you evaluate the person on several fronts.

Do you recognize them?

If not, do they work for your company or a frequently contacted company?

Do they know someone you know?

It’s easy to turn most those answers into yes.

LinkedIn Makes Resume Padding and Scamming Easy

We didn’t follow through with the Google recruiter.

Google would quickly realize our profile was fake.

After all, we used a photo of a person who doesn’t exist!

But you don’t need an entirely fake profile to benefit from LinkedIn’s policies.

You could pay for connections and endorsements.

That could help you get a job interview.

Resume padding is an old trick, and this is the digital version.

That’s bad for everyone.

As recruiters get burned, they’re less likely to trust LinkedIn and may turn to other recruiting methods.

Getting a job might not always be the name of the game.

The scammer could simply have created a fake LinkedIn profile.

Instead, that company would have to plead its case to LinkedIn.

For example, LinkedIn could let companies verify their employees and provide better tools for removing rogue employees.

Then it could put a stop to the practice.

Other social networks already watch for fake accounts.

But, until LinkedIn takes action, you should look harder at every connection request.