Git uses branches to isolate development streams, to prevent the stable release branch from becoming polluted.

Bringing work in a branch into the main stream means merging branches.

Here’s how you do it.

Master Hands/Shutterstock

What Is a Merge in Git?

Git was designed to make branching simple and fast.

In contrast to other version control systems, branching on Git is a trivial matter.

On multi-developer projects especially, branching is one of Git’s core organizational tools.

This usually contains the stable version of your code base.

Isolating these changes from your stable code version makes perfect sense.

At that point, you’re gonna wanna merge your branch into the master branch.

That work is completed, and we’ve tested our code.

It all works as expected.

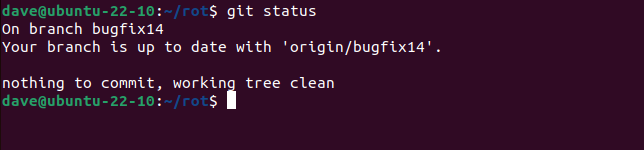

There’s a little preparation to be done before we perform the merge.

To do this we’ll use the

command.

All of those indicate that the branch is up to date, and we’re clear to proceed.

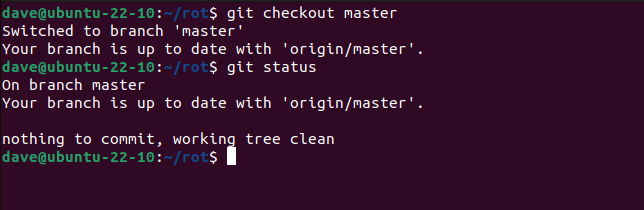

Checking out the branch we’re going to merge into simplifies the merging process.

It also allows us to verify it is up to date.

Let’s have a look at the master branch.

We get the same confirmations that the “master” branch is up to date.

Performing a Merge

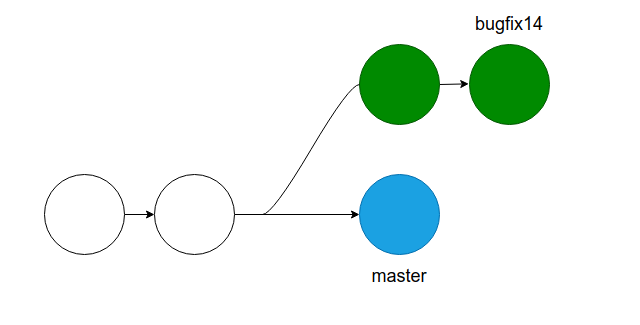

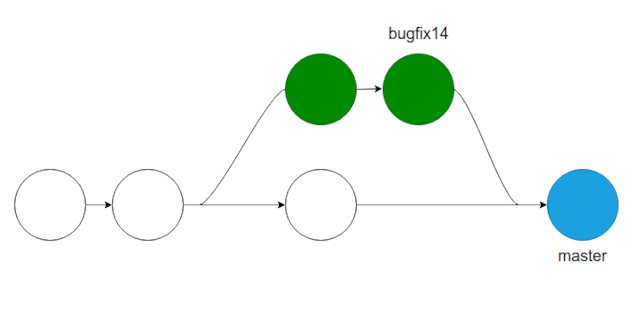

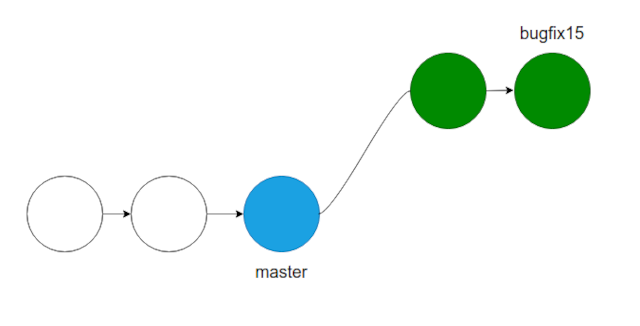

Before we merge, our commits look like this.

The “bugfix14” branch was branched from the “master” branch.

There has been a commit to the “master” branch after the “bugfix14” branch was created.

There have been a couple of commits to the “bugfix14” branch.

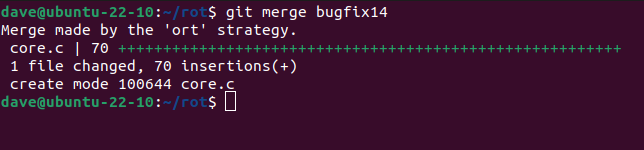

We can issue the command to merge the “bugfix14” branch into the “master” branch.

The merge takes place.

In this instance the merge command performs a three-way merge.

There are only two branches, but there are three commits involved.

They are the head of either branch, and a third commit that represents the merge action itself.

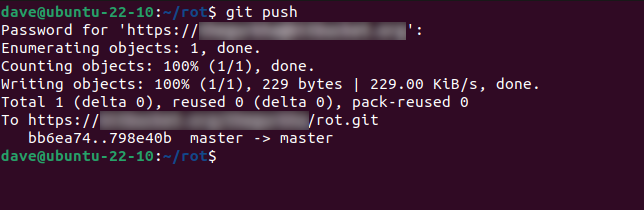

To update our remote repository, we can use the git push command.

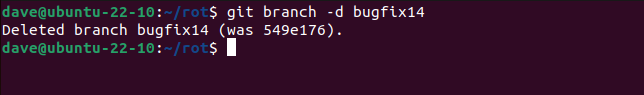

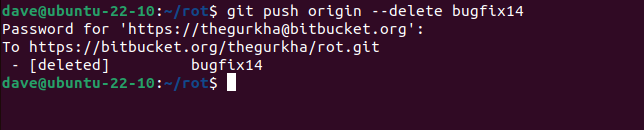

Some people prefer to delete side branches once they’ve merged them.

Others take care to preserve them as a record of the true development history of the project.

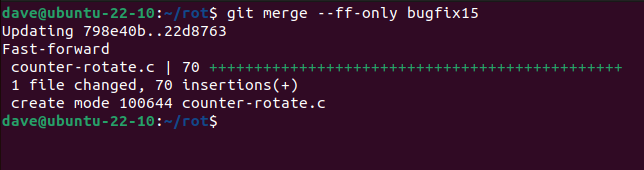

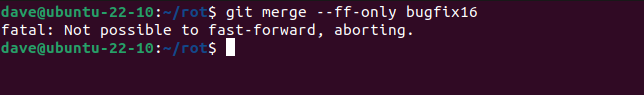

We can use the usualgit mergecommand:

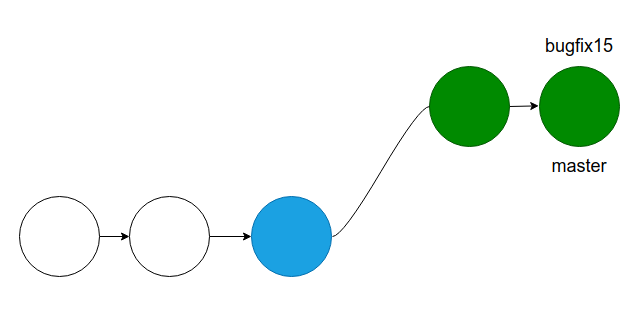

That gives us this result.

The option is–ff-only(fast-forward merge only).

Git will complain and exit if it isn’t possible.

Human interaction is required to address the conflicting edits.

But “rot.c” has been changed in the “master” branch too.

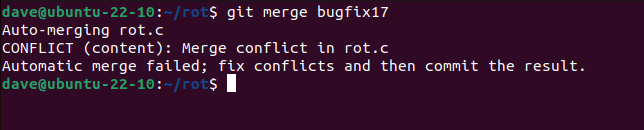

When we take a stab at merge it, we get a warning that there are conflicts.

Git lists the conflicting files, and tells us the merge failed.

Git has done some work to help us.

For each conflict, you should probably choose which set of edits you’re going to keep.

You must edit out the code you’re rejecting, and the seven-character lines that Git has added.

We’re going to keep the code from the “bugfix17” branch.

After editing, our file looks like this.

We can now carry on with the merge.

But note, we use thecommitcommand to do so, not themergecommand.

We commit the change by staging the file and committing it as usual.

We’ll check the status before we make the final commit.

The merge is complete.

We can now push this to our remote repository.

Merging branches is easy, but dealing with conflicts can get complicated in busy, larger teams.

Sadly, Git can’t help with that.